Janice asked a question that I get quite often, “Dear Derek, should I name a trust as my 401k or IRA beneficiary?”

A: Janice, it depends on what the objective is related to your wealth transfer plan. Wealth grows in a tax-deferred environment inside an IRA. When it is distributed from the IRA, the taxpayer generally either spend the funds or reinvests it in a taxable account. This means that for taxpayers who don’t need their IRA funds for support, the more slowly the funds can be withdrawn from the IRA, the faster they can accumulate wealth. The reason is simply that wealth grows faster in a tax-deferred account than in a taxable account. In the tax-deferred account, it grows at its pre-tax rate of return, and in a taxable account, it grows at its after-tax rate of return.

Unfortunately, many advisors are not proficient when it comes to trust planning and their effects related to distributions to owners of traditional IRAs. Once an IRA owner reaches age 72, they must begin receiving payments and the payment percentages are locked in. The IRA owner does have control over who the beneficiaries are, however, and this creates an important planning opportunity. The younger the designated beneficiary of the IRA is, the smaller the annual payments can be and the more wealth that is left to grow in the tax-deferred environment (again assuming that the beneficiary does not need the funds); thus, the longer the life expectancy of the designated beneficiary, the better. Careful planning to minimize required minimum distributions (RMDs) is particularly important when a trust is named as the IRA beneficiary.

Please understand that almost any person or entity can be the beneficiary of an IRA, but if the beneficiary is a nonperson with a life expectancy of zero, like an estate or trust, the IRA will be treated as having no “designated” beneficiary. If so, the full value of the IRA must be paid out (1) over the IRA owner’s hypothetical life expectancy if he or she had reached her required beginning date before he or she died, or (2) by the end of the fifth year after the IRA owner’s death if the IRA owner had not reached his or her required beginning date (age 72 or the date of retirement of later).

Trusts as IRA Beneficiary

IRA owners generally name individuals as beneficiaries of their IRAs because trusts increase complexity and raise potential problems; these include:

- The difficulty of qualifying a trust as a designated beneficiary;

- Legal and trustee fees;

- The necessity of filing trust income tax returns;

- The possibility that income tax will be higher on distributions to a trust than distributions to an individual because of the compressed tax brackets for trusts;

- The administrative difficulty of determining how to allocate distributions between income and principal; and

- Determining whether the trust or its beneficiaries are subject to tax.

Naming an individual as beneficiary may lead to more serious problems, however. Such problems may include:

- The IRA owner has no control over how the assets will be managed or distributed after his or her death;

- The IRA owner cannot protect the assets from creditors after his or her death;

- The IRA owner has no control over who receives the IRA payments after the death of the primary beneficiary; and

- The IRA owner has no control over how fast payments are made.

Naming a trust as beneficiary can solve all of these problems. Thus, IRA owners concerned about any of the issues listed above should give serious consideration to this option. Careful planning is necessary, however, to create the best possible result for the family and to avoid traps for the unwary. There is a special rule under Reg. § 1.401(a)(9)-4, Q&A 5 that permits an IRA owner to name a trust as the beneficiary of his or her IRA (and not the trust itself) treated as the designated beneficiary for RMD purposes if four requirements are satisfied:

- The trust is valid under state law, or would be but for the fact that there is no corpus;

- The trust is irrevocable or will by its terms become irrevocable upon the death of the IRA owner;

- The beneficiaries of the trust can be identified from the trust instrument; and

- Proper documentation has been provided to the plan administrator.

If the trust does not meet all four requirements, the IRA will be treated as having no designated beneficiary. Naming a Qualified Terminable Interest Property (QTIP) Trust as IRA Beneficiary An IRA owner who wants his or her spouse to benefit from his or her IRA but is concerned that he or she will not be able to manage the assets or will pass remaining assets to children of his or her first marriage when he or she dies should think about naming a QTIP trust as his or her IRA beneficiary. By transferring the IRA to a QTIP trust, the owner can provide the spouse with an income interest for life but no power to designate remainder beneficiaries upon his or her death. If properly structured, a QTIP trust enables the IRA owner to defer estate taxes until the death of the surviving spouse without giving up control over where any remaining assets go at his or her death.

A QTIP trust must meet the same four requirements as any other trust to qualify the spouse as a designated beneficiary. In addition, the planner must make sure that the trust qualifies for the marital deduction. A QTIP trust qualifies for a marital deduction under IRC § 2056(b)(7) if all of the following requirements are satisfied:

- The surviving spouse is entitled to all income from the property, payable at least annually (IRC § 2056(b)(7)(B)(ii)(I);

- No person has the power to appoint any part of the property to any person other than the surviving spouse (IRC § 2056(b)(7)(B)(ii)(II));

- An election is made on the decedent’s estate tax return to treat the trust property as QTIP (IRC § 2056(b)(7)(B)(v));

- The value of the trust is included in the surviving spouse’s estate when he or she dies (IRC § 2044); and

- The trust must either hold productive assets or give the surviving spouse the power to require the trustee to make the assets productive (Reg. § 20.2056(b)(f)(4) and PLR 9717005).

Requirements 2-5 are relatively straightforward. Having an IRA as a trust asset adds considerable complexity to requirement (1), however. The IRS has provided the following guidelines to help planners understand the requirement:

- Reg. § 20.2056(b)-5(f)(1) provides that requirement (1) is satisfied if the surviving spouse is entitled for life to income as determined by applicable local law that provides for a reasonable apportionment between the income and remainder beneficiaries of the total return of the trust and that meets the requirements of IRC § 1.643(b)-1.

- Reg. § 20.2056(b)-5(f)(8) provides that the surviving spouse is entitled to all income for life, payable at least annually if the spouse has the right to require that the trust distribute all income to him or her at least annually, even if no distributions are actually made.

- Reg. § 1.643(b)-1 provides that the term “income” means the amount of income of the estate or trust for the taxable year determined under the terms of the governing instrument and applicable local law. Allocations made between income and principal under applicable state law will be respected if the state law provides a reasonable apportionment between the income and remainder beneficiaries of the total return of the trust for the year.

Revenue Ruling 2000-2 provides that if an IRA is payable to a trust, both the IRA and the trust must meet the marital deduction requirements. This will be the case if the surviving spouse has the power, exercisable annually, to compel the trustee of the QTIP trust to withdraw the income earned on the IRA assets and to distribute that income (along with the income earned on the trust assets other than the IRA) to the surviving spouse. In other words, the surviving spouse must be entitled to both the income of the trust and the income of the IRA.

If the surviving spouse exercises this power, the trustee must withdraw from the IRA the greater of: (a) the amount of income earned on the IRA assets during the year, or (b) the RMD and distribute at least the income to the surviving spouse (Rev. Rul. 2000-2). If the surviving spouse does not exercise the power, the trustee is required to withdraw from the IRA only the RMD (Rev. Rul. 2000-2). Any IRA income in excess of the RMD can stay in the IRA to grow in a tax-deferred environment. Note that the RMD only needs to be distributed from the IRA to the QTIP and not from the QTIP to the surviving spouse (Reg. 1.401(a)(9)-8, Q&A 11). In light of this requirement, advisors should review the governing instrument of a QTIP to make sure the surviving spouse is entitled not only to all income of the QTIP trust but also to all the income of the IRA.

Naming a Credit Shelter Trust as IRA Beneficiary

A common estate planning strategy is to combine a marital trust with a credit shelter trust to make full use of both spouses’ applicable exclusion amounts. The credit shelter trust ordinarily gives the trustee discretion to pay income to the surviving spouse pursuant to an ascertainable standard and possibly also principal, with the remainder interest passing tax-free to the children.

IRAs often comprise the great bulk of an estate so the only way to fund the credit shelter trust is to use IRA assets. This may create a difficult planning problem, however. If the credit shelter trust is not fully funded, the estate tax could be increased in the estate of the second spouse to die (although this concern has lightened somewhat given the newly available portability election). Also, by making the credit shelter trust the beneficiary of the IRA, it generally shortens the stretch-out period for distributions and decreases the amount of wealth that can be accumulated for the family. The reason is that it prevents the family from using the spousal rollover option.

In certain circumstances, it may be advantageous for an IRA owner to convert to a Roth IRA immediately prior to death in an attempt to reduce the value of his or her taxable estate. In turn, the Roth IRA could be used to fund the deceased IRA owner’s credit shelter trust. If both of these strategies are employed, this will result in lower overall taxes (estate and income) not only for the decedent IRA owner but also for his or her beneficiaries. One of the downsides of naming a credit shelter trust as an IRA beneficiary is that IRA distributions may be taxed at a higher marginal income tax rate than they would be if they were paid to the surviving spouse because of the compressed income tax rates of the trust. Trust income could be shifted to the surviving spouse by distributing to him all the income and giving the trust a DNI deduction. The effect would be to have the income taxed at the spouse’s marginal tax rate which might be lower than the trust’s tax rate. However, large distributions to the surviving spouse would bring amounts back into his or her estate and defeat the purpose of the credit shelter trust. Moreover, regardless of who paid the income tax, the full amount of the applicable exclusion amount would not be used because some would be lost to income tax when distributions were made. This problem could be solved by converting the traditional IRA to a Roth IRA. No tax would be paid on the distributions to the surviving spouse so the exemption amount could be used to its full advantage.

Spousal Rollover Option

The Internal Revenue Code provides a very favorable option when the surviving spouse is the sole beneficiary of an IRA. The spouse can roll the IRA over into his or her own IRA and name new beneficiaries (e.g., his or her children), greatly increasing the deferral period (IRC § 402(c)(9)). As an added benefit, if the IRA owner dies before the surviving spouse reaches his or her required beginning date, he or she can delay the start of distributions until he or she reaches age 72 (Reg. § 1.401(a)(9)-3(a)(3)(B)).

The IRS has taken the position, however, that the option is only available if the surviving spouse has total control over the disposition of the plan assets (PLR 200944059). Thus, the spouse must ordinarily be the outright beneficiary of the IRA pursuant to a specific beneficiary designation (Reg. § 1.408-8, Q&A 5(a)). If anyone other than the surviving spouse controls the IRA proceeds (e.g., a trustee other than the surviving spouse), a rollover is generally not available (PLR 9851050). Giving the surviving spouse the power to withdraw the trust assets would make it possible to do a spousal rollover (PLRs 200950053 and 200928045), as would making the spouse the trustee of the credit shelter trust with the power to control distributions. If the spousal rollover is not available, the life expectancy of the surviving spouse would have to be used instead of the life expectancy of the oldest child, and distributions to the surviving spouse would begin when the IRA owner died.

Disclaimer Planning by the Surviving Spouse The decision as to whether the surviving spouse should be the IRA beneficiary or whether he or she should disclaim can be delayed until nine months after the IRA owner dies. If the surviving spouse is named the primary beneficiary and the credit shelter trust the contingent beneficiary, the spouse could either continue to be the primary beneficiary or disclaim, letting the IRA pass to the trust.

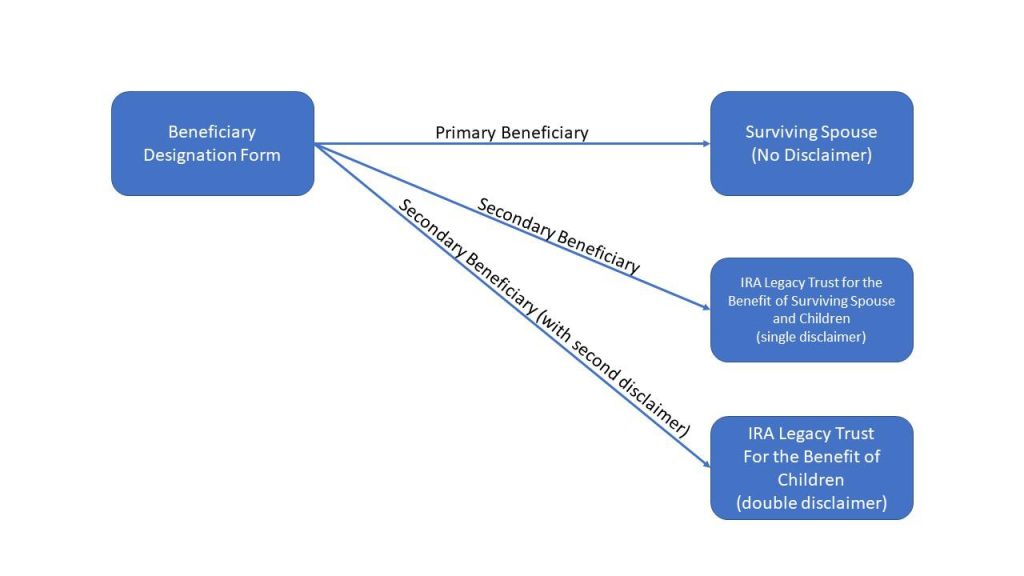

Further, the “Double Disclaimer Strategy,” is designed to allow the surviving spouse to choose among the following possibilities:

- Retirement plan assets will pass to the surviving spouse as a direct beneficiary, and he or she will be allowed to roll those assets into a new IRA and name the beneficiaries of his or her choice for that new IRA.

- In the event of a disclaimer, retirement account assets will pass to a stand-alone credit shelter trust that includes the surviving spouse as a beneficiary who will receive the financial protection provided by those assets while allowing the assets to be protected from future tax by full use of the deceased spouse’s unified credit.

- In the event of a second disclaimer, retirement account assets will pass to a stand-alone credit shelter trust for the benefit of children, allowing the children to take required distributions based upon the oldest child’s life expectancy.

Please refer to the example illustration below:

To make this strategy work, both the beneficiary designation and the trust that may become the beneficiary must be carefully drafted to comply with the complex tax rules that qualify the trust as a potential beneficiary and allow the disclaimer to have its intended effect. First, the Beneficiary Designation Form must provide that although the surviving spouse is the primary beneficiary, in the event that he or she disclaims his or her interest, it will be paid to the credit shelter trust for the benefit of spouse and children.

The credit shelter trust for the benefit of spouse and children must be set up to qualify as a designated beneficiary and provide that beneficial distributions of income or principal or both may be made to the surviving spouse. In addition, the beneficiary designation form must provide that in the event that the surviving spouse disclaims his or her beneficiary interest in the credit shelter trust, the retirement asset proceeds will be paid in separate shares to the children, or in the alternative to qualifying trusts for their benefit.

Each scenario has its own potential benefits, which can be chosen, depending upon the laws and priorities in existence at the first spouse’s death. These include the following:

Scenario One: The surviving spouse does not disclaim

If the surviving spouse does not disclaim the retirement account, he or she will be the beneficiary. He or she will then have complete discretion to make withdrawals based upon his or her needs and income tax circumstances. The surviving spouse would also be able to roll over the account into an account set up and maintained in his or her name as opposed to keeping it titled as an inherited IRA. The retirement account will have minimum distributions calculated each year based upon the surviving spouse’s life expectancy in that year. This strategy will therefore produce lower required minimum distributions and, thus, a larger benefit from tax-deferred growth within the retirement account than in the second scenario.

In addition, the surviving spouse will be able to name new beneficiaries for the retirement account who will inherit their shares upon the surviving spouse’s death. If the surviving spouse performs a spousal rollover and carefully sets up his or her beneficiary designations, the new beneficiaries, who will most likely be children, will be allowed to take distributions from their shares of the retirement account over their own individual life expectancies. IRA Legacy Trust for the Benefit of Surviving Spouse and Children (single disclaimer) Secondary Beneficiary IRA Legacy Trust for the Benefit of Children (double disclaimer)

Scenario Two: The surviving spouse disclaims all or a portion of the account.

If the surviving spouse enters a single disclaimer, he or she will no longer be the sole beneficiary of the retirement account and will not be able to roll the account over to treat it as his or her own. However, the retirement account will now be paid to the credit shelter trust that will be able to use the deceased spouse’s available unified credit. If the retirement account is paid to this trust, it will not be subject to death or transfer tax upon the surviving spouse’s death, no matter what changes Congress makes to the tax rates or the exemptions and credits.

The payments from the retirement account can be used for the benefit of the surviving spouse and the children, or if the grantor chooses, the assets of the trust can also be used for the benefit of other family members.

Minimum distributions will be calculated based upon the surviving spouse’s life expectancy in the year following the year of the deceased spouse’s death. Because other persons are also beneficiaries (the children), calculations will use the first-year factor reduced by one for each subsequent year. After the surviving spouse’s death, the required distributions will continue to be calculated based upon his or her life expectancy.

This scenario allows the retirement account to be used for the benefit of the surviving spouse, while still protected from the further estate or transfer tax. It should be given strong consideration if the deceased spouse dies without other assets that can be used to take full advantage of his or her unified credit exemption equivalent.

The surviving spouse would not have to disclaim the entire retirement account but instead could disclaim only a portion of the account. The portion not disclaimed could be rolled over into a retirement account, set up, and maintained in the surviving spouse’s name.

Scenario Three: The surviving spouse disclaims twice

If the surviving spouse disclaims his or her interest as a direct beneficiary of the IRA, as well as his or her interest in the credit shelter trust, the beneficiary designation may provide that the retirement account will then be paid either directly to the children (or grandchildren) or to the credit shelter trust solely for the children’s benefit.

In this scenario, not only may the full unified credit equivalent be used, but also the retirement account will have required distributions based upon the age of the oldest child. This will usually produce the lowest required distributions and therefore the largest benefit from the continued tax deferral of the investments in these accounts.

Since the surviving spouse will receive no benefits under this scenario, the “double disclaimer” strategy will only be used where he or she has other assets to provide for his or her financial needs. When this strategy is employed, the value of the wealth transferred is greatly enhanced by the lengthy deferral of withdrawal that is possible when younger individuals are named as beneficiaries. This arrangement also has some possible downsides:

- The surviving spouse makes the decision rather than the IRA owner;

- A timely disclaimer may not be made by the surviving spouse even though it might be advisable; and

- The surviving spouse may decide to keep the benefits even if a disclaimer would be best for the family.

Correcting Unfavorable Beneficiary Designations

Ideally, the IRA owner will plan ahead and have a favorable designated beneficiary when he or she dies. Mistakes are often made in naming beneficiaries, however, shortening the deferral period.

Fortunately, beneficiary designations can be improved with post-mortem planning. Because only individuals or entities who are beneficiaries both when the IRA owner dies and on the following September 30 of the year following the IRA owner’s death are countable for purposes of determining a designated beneficiary, there is a window period for correcting unfavorable beneficiary designations. This window period, which could last from just over nine months to just under 21 months, can be used to eliminate unwanted beneficiaries that shorten the payout period.

Beneficiaries can disclaim an interest in an IRA if (1) they meet all the general requirements for a qualified disclaimer under IRC § 2518, and (2) the disclaimer is made by September 30 of the year following the IRA owner’s death. The general requirements for a qualified disclaimer are as follows:

- There must be an irrevocable and unqualified refusal by a person to accept an interest in the property;

- The refusal must be in writing;

- The written refusal must be given to the transferor of the interest within nine months after the date on which the transfer creating the interest is made;

- The disclaiming person hasn’t accepted the interest or any of its benefits; and

- As a result of such refusal, the interest passes without any direction on the part of the person making the disclaimer and passes either (a) to the spouse of the decedent, or (b) to a person other than the person making the disclaimer (IRC § 2518(b)).

Note that as a practical matter, the September 30 deadline does not really change the general requirements. The nine-month period can never end after September 30 of the year following the IRA owner’s death and, in most cases, will expire long before that date. A second option is to cash out a beneficiary’s interest before September 30 of the year following death. This is done by simply paying the beneficiary to be eliminated such a beneficiary’s interest in the IRA. This method might be used to eliminate non-individuals like charities that might be unwilling to disclaim.

Historically, disclaimers were generally used to eliminate an older individual as a countable beneficiary. This made a younger person with a longer life expectancy the designated beneficiary; thus, decreasing the required minimum distributions. Following the SECURE Act, distributions to non-spousal beneficiaries must generally be made within 10-years after the IRA owner dies, eliminating much of this planning.